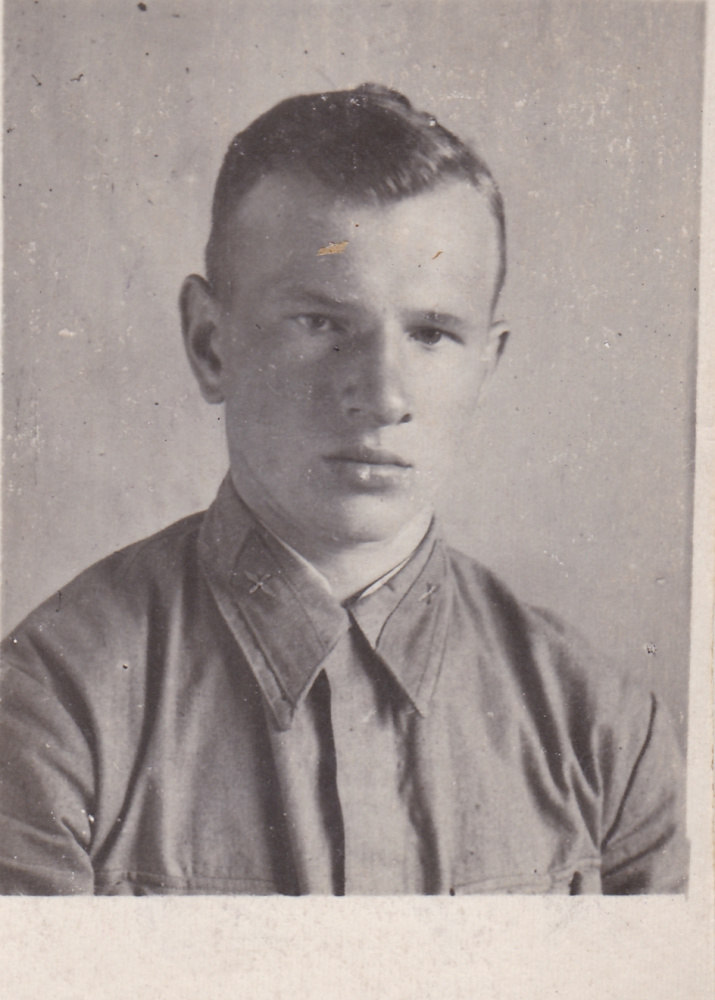

Separately, I want to dwell on the story of the Verkhoyansk Robinson Crusoe – the pilot of the 3rd Air Transport Regiment, Senior Sergeant Nikolai Dyakov. His plane made an emergency landing in the taiga, where the pilot spent 40 days waiting for evacuation.

Emergency landings – and, as you understand, they happened on the ALSIB Air Route – often had a tragic outcome. Difficult weather conditions, a malfunction of the aircraft and, finally, a landscape completely unsuited for landing, much less an emergency one, often led to a sad ending. So it was with Alexey Fedorenko.

The case, by the way, is very similar – in both situations it was a P-40 Kittyhawk and a landing with a non-working engine. Fedorenko landed with the landing gear released and this actually minimized his chances of a successful outcome. The crew of the C-47 Douglas of Fyodor Ponomarenko, obviously, also tried to make an emergency landing.

Nevertheless, "happy accidents happened." In particular, Viktor Glazkov, a C-47 radio operator, describes his emergency landing as follows: "...The flight mechanic reported that there was enough fuel for 10 minutes of flight. We descend to a height of 150-200m. The commander turned on the headlights to avoid obstacles during landing, and then... both engines cut out – the fuel has run out. The commander lands the plane on some tiny clearing overgrown with small bushes. Parallel to our landing course, we see the bed of a small river, which, having made a sharp turn ahead, crosses our course. The speed that the plane still had and the use of the elevator made it possible to fly over the riverbed. The Lena River bank rolls ahead. The commander and the co-pilot are stepping on the brakes with all their might. The aircraft trembled, threatening to nose over, froze in an unstable equilibrium and then fell on its tail."

Interestingly, five days after refueling, the crew managed to take off on the aircraft from the ice.

By December 1941, Senior Sergeant Nikolai Dyakov could well have been called a fairly experienced pilot: "At the front, he made 25 combat flights to scout and attack enemy troops. He was awarded the Order of the Red Banner and appointed a flight commander. On the air route since August 1942. He flies boldly and confidently, his piloting technique is excellent, he shows resilience in long flights. Ferried 16 P-39 aircraft."

On December 9, 1942, during the flight of a group of aircraft on the Seimchan–Yakutsk section, the rubberized hoses of the oil radiator of the P-40 Kittyhawk aircraft piloted by Dyakov burst. Which, in general, is not surprising – neither metal nor rubber could withstand such extremely low temperatures. A minute – and the engine will cut out. Dyakov decided to make an emergency landing. He chose the riverbed between two mountain ranges and, having stirred up tons of packed snow, landed the plane.

The most dangerous sections of the ALSIB were the Chukotka section and the Seimchan–Yakutsk section. This is the highest mountainous area from Fairbanks to Krasnoyarsk: from the west, the Verkhoyansk Range, from the east, the Gydan. Elevations of 2600m. In winter, frosts reaching up to -55°C. Oymyakon – it was a reserve airfield on the route – was generally considered a pole of cold, where low temperatures were also accompanied by fogs.

Almost all chroniclers write about severe frosts and equipment failures in such conditions.

In several decades, this story has been filled with so many delicious details that sometimes it seems that the authors shared with Nikolai Dyakov absolutely all his adventures. But I will try to rely on the facts, using the help of the historian of the ALSIB Vyacheslav Filippov. He provided archival documents from which it is possible to compile a chronology of events and conclude what aided the survival. In total, the pilot stayed in the taiga for 40 days. On December 9, 1942, he made an emergency landing, and on January 19, 1943, he was rescued by local residents. The nearest hose was almost 100km away; snow was at least waist-deep. In my opinion, the right decision was to stay at the crash site so that it would be easier to notice the pilot; and you could hide in the cockpit in case of an attack by wild animals. In any case, they would have been looking for the pilot.

And they were really looking for him, but they couldn't find him right away: "A search was organized for the plane, and it was discovered by the crew of the B-25. To identify himself, Dyakov fired more than 20 colored flares. The B-25 didn't spot the exact location. The next day, a Li-2 could not get into that area because of severe weather conditions. Dyakov himself, not taught how to use the radio, did not turn on the radio receiver and did not make a call to report an emergency landing." Most likely, "not taught to use the radio" refers specifically to this type of aircraft, and not to radios in general – by this time, Nikolai Dyakov had successfully ferried 16 P-39 Airacobra aircraft and he probably knew how to use the radio.

A few days later, the plane that crashed in the mountains was discovered by the pilot of the R-5 Shubin. From that moment until his rescue by local residents, supplies were dropped for Dyakov from time to time from a plane with clothes, food, and all necessary for survival. According to the testimony of the participants of the flights, even in such a deserted area, the pilots who survived the emergency landing were searched for and were not abandoned to the mercy of fate – everyone who continued to fly along the air route was sure that people would also be looking for them.

We mainly consider the technical aspects of such cases – the landing conditions, the landscape, weather conditions, the nature of the malfunction, etc. I have always been interested in the psychological aspect of such situations: how did people who found themselves in extreme circumstances manage to survive in a hostile environment?

Like, for example, the story of pilot Alexey Petrovich Maresyev, about whom we made a film, having thoroughly researched the absolutely unknown episodes of his life (including the so-called "forest episode").

I participated in an expedition along the ALSIB at the Chukotka stage and did not get to Yakutia. It's a pity – I would have had a chance to try to find Nikolai Dyakov's plane myself, and having found it, evaluate the reasons for the miraculous rescue. There are few chances to land a plane with a non-working engine in this area – Nikolai Dyakov did not miss his chance.

From the archive materials: "Accident of the R-40 piloted by Dyakov, 09.12.1942. It was not possible to evacuate the plane, subsequently the plane sank during the spring ice drift. The pilot was taken out on dogs by a specially equipped expedition."

If the plane could not be evacuated, then it can be found. And a few days ago, the head of the Yakutia stage of the RGS’s expedition Alexey Efanov told me that the plane had been found. The place of the crash was the confluence of the Dodae and the Teberden rivers. However, not the whole plane, but only the wing. But it was the wing with a retracted landing gear – the pilot understood that landing on the belly gives more chances to survive. With the landing gear released, as the pilots say, the plane would "crumble" – reduce landing speed. And if the landing gear touched the ground, the plane would have nosed over.

Other fragments could not be found. In 80 years, the plane was pulled apart by annual floods into parts and kilometers. And the wing turned out to be clogged with sand and pebbles – the efforts of eight people were not enough to turn it over.

The life of Nikolai Dyakov has become steeped in mythical details. According to one version, the pilot was treated for a long time, his fingers were amputated. Subsequently, he was restricted from flying and dismissed from the service for health reasons.

In fact, his life was going quite well until 1968. It seems to me that then, on December 9, 1942, Nikolai Dyakov was saved thanks to experience, composure, and faith. He escaped to die in a plane crash 23 years after the war.

Reference

Dyakov Nikolay Aleksandrovich

Born in 1922. In the Red Army since 1940. Graduated from Chuguev Military Aviation School (1941). At the front from March to June 1942 – pilot; flight commander of the 295th Fighter Aviation Regiment, North-Western Front. On the air route since 08.28.1942 as the pilot of the 3rd ATR, 4th ATR.

After demobilization from the Soviet Army (1946), he worked as a co-pilot in the 14th Heavy Aviation Unit of Yakutia Civil Aviation Administration. Since 1950, the commander of the aircraft of the 46th Heavy Aviation Unit, since 1952 – in the 139th Heavy Aviation Unit pilot instructor, deputy commander of an Aviation Squadron, since 1954 – the commander of an Aviation Squadron. Since 1960, he has been an instructor pilot of the Logistic Departmen-17. In 1966-1968 – commander of the AN-24 aircraft, instructor pilot of the 271st Air Squadron.

He died in a plane crash in 1968.

Petty officer, second lieutenant, lieutenant.

He was awarded the Order of the Red Banner (30.08.1943), the Order of the Patriotic War of the Second Degree (19.08.1944), the "Badge of Honor" (1953), medals "For the Victory over Germany" (1945), "For the Victory over Japan" (1945), the badge "Excellent Worker of Aeroflot" (1964). Awarded the title of Honored Transport Worker of the Yakut Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (1965).

From the award certificate from 10.03.1943:

"At the front, he made 25 combat flights for reconnaissance and assault of enemy troops. He was presented to the Order of the Red Banner and appointed a flight commander. On the air route since August 1942. He flies boldly and confidently, his piloting technique is excellent, he shows resilience in long flights. Ferried 16 P-39 aircraft. 09.12.1942 when flying over the Verkhoyansk Ridge on the Seimchan–Yakutsk section, when the oil pressure in the engine dropped, despite the terrain unsuitable for landing, decided to land to save the plane. Spent 10 days by the plane, waiting for help, leading a half-starved life. Despite the difficult conditions and a significant loss of strength, after a few days of rest, he began to refuel the aircraft again. Worthy of being awarded the Order of the Red Banner.

The commander of the 4th ATR, Lieutenant Colonel Smolyakov. 10.03.1943.”

From the award certificate from 07.05.1944:

"On the air route in the 4th ATR since August 1942. Ferried 146 P-40 and P-39 combat aircraft. Of these, 23 along the route Seimchan–Yakutsk; 108 along the route Yakutsk–Kirensk; 15 along the route Kirensk–Krasnoyarsk. 633 flight hours on the air route. The piloting technique and blind training are excellent.

For the excellent performance of the government task on the ferrying of aircraft in the conditions of the Far North, he deserves to be awarded the Order of the Patriotic War of the First Degree.

The commander of the 4th ATR, Lieutenant Colonel Vlasov."

This guy personally, during the three years of the existence of the ALSIB airway, ferried 146 combat aircraft, of which, imagine, five aviation regiments were formed at the front! As you understand, no one was awarded the Order of the Red Banner and the Order of the Patriotic War of the First Degree just like that.

But nevertheless, the fact is that the pilots of the transport regiments were not officially considered participants in the war and the benefits were not extended to them. Their contribution to the victory is quite obvious to us, as evidenced by the total number of aircraft that were ferried along the ALSIB – 8094! 114 pilots did not return from the flight.

As for what is the secret of surviving in extreme circumstances, the answer, I think, should be sought from the Austrian psychologist Viktor Frankl, who went through the horror of the Nazi concentration camps. Continuing his professional activity even in such circumstances, he came to the conclusion that it was not the healthiest and strongest who survived at all. The motto of his work in the concentration camp may be the words of Friedrich Nietzsche: "He who has a why to live for can bear almost any how." In his book "Yes to Life: In Spite of Everything ", published after the war, he deduced the secret of survival, which remains relevant today: "There is nothing in this world, I venture to say, that would so effectively help one to survive even the worst conditions as the knowledge that there is meaning in one's life."

The author thanks Vyacheslav Filippov, Alexey Efanov, and Alexander Klimov for their help in preparing the material.

To be continued.

Alexey Nikulin